Good Enough Black Mothering

On tears and growth

Again, credit to a fellow SubStacker for help with editing, same as with the last post. In gratitude.

On Mothering

I went into labor with my youngest child on the same day my mother completed her 77th cycle around the sun. That day felt sacred and ominous, as I oscillated between more emotions than I can name. I was, of course, beyond excited to meet the new human being that the universe had decided to entrust to me and my husband. Another soul for us to nurture, love and provide the scaffold for them to become the best version of themselves.

We had just closed on our second home, this time in California. We moved there—after being forced, by way of financial insecurity—from our first purchased homestead in the eastern cape of South Africa. Grief was, and is, still heavy on my chest from the loss of the potential 73 acres in Xhosa land would have provided spiritually and psychologically for myself and my family. Against all odds, I found myself trying to find hope in a land that often offers up early death for those that look like me.

The day my youngest daughter was born, I was excited, yes. But I also felt a strong sense of foreboding hovering, as if the universe was trying to remind me again, through my mother, of our impermanence. I feel blessed that she is still here on this side of the dry soil, relatively healthy, living her best life with her partner, my stepmother.

Motherhood has changed me in so many ways. One of the unexpected gifts has been the way in which it has increased my feelings of compassion for my own mother and an understanding of how much she put into raising me. I remind myself that she was “good enough”, even if she was far from great. In psychology “good enough mothering” was a concept credited to Winnicott, a psychoanalyst and pediatrician, who described the need for mothers to gradually introduce increasing levels of frustration that allows for children to develop an appreciation of an external world that does not always acquiesce to their needs and wants. My mother, like many other Black mothers of her generation, parented through emotional silence masked as resilience. She modeled “strength” in the form of absent emotional vulnerability. I am grateful that she did not have to parent me alone, that my father and my mother’s mother were both strong sources of support and loving affection. We were blessed to have a tribe of Sister-Aunties and Brother-Uncles within the black Muslim community, that poured into us as children. Those that helped us to become whole by filling the gaps of emotional absence offered up by my mother in my younger years.

A Cry Passed Down

While in graduate training I ask my mother about what she could recall about that baby phase of my life. All that came up for her was that my cry was so disconcerting that a friend of hers described it as more of a shriek. My mother also told me that in my first years, I did not get the attention I wanted when I wanted due to all the obligations she and my father were shouldering.

I was born into a family with two older siblings, both younger than three, while my mother was also a graduate student in pursuit of her master’s degree in education. When my mother first described my shrieks, I assumed, that I developed this cry out of necessity. It wasn’t until I heard the first shrill-like cries from my youngest within the first 24 hours of her life, reaching an octave more piercing than her older two siblings ever mustered, that I began to question my assumption. My daughter’s cry, one clearly born from biology rather than experience, triggers an instinct, in me, to shoosh rather than soothe. An instinct, because of my own childhood, I fight against successfully most days.

I wonder, still, how much of my inborn temperament contributed to the way my mother engaged with me as a child. I know she modeled a love she was gifted growing up, a love that was ill equipped to hold gently the big emotions that I came into this world expressing openly and often. I try my best to hold gently the oscillations of energy and mood that my three little one’s offer up in supplication for their needs. Sometimes this means a firm embrace to keep them from striking out physically, sometimes a hug, sometimes I simply listen and offer an emphatic acknowledgement that their suffering matters, even if I can’t remedy the cause. Sometimes, when I am overstimulated, I miss the mark completely and lose it in volume and tone, with a far less than gentle response. Often that happens when all three are falling apart simultaneously in a cacophony of crying, yelling and tears. In these moments I collect myself afterwards with a few deep breaths and return with an apology and a hug. My children know that Mommy is still learning how to be a better Mommy. I am humbled when my eldest offers up feedback in advancement of this endeavor towards growth. I understand, now, that there are no perfect parents. That these moments are integral parts of how my journey towards being “good enough” materializes in the now.

“Good Enough”

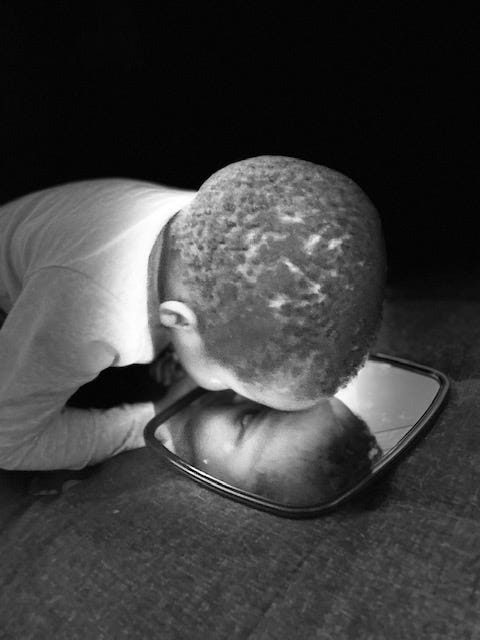

I felt relief to learn that I just had to just be “good enough” as a mother to my children, not perfect. That children need to experience disappointment, learn that the world does not bend to their every whim. That I am responsible for teaching my children, among other things, resilience, from a place of nurturing love. A necessary skill to navigate the ever present and changing waters of life’s upsets and losses. I do believe my mother has been and continues to be “good enough” for me. I see my mother as one of the many blessings in my life, a soul sent to help guide me on this journey, and I pray I can continue to improve upon the model she provided for me with all three of my children. I try to pay attention to who they are at the core and provide an active intentional love that allows them to be seen, to thrive, to grow confidently into themselves. One good cry at a time.